This article about how South Korea managed to gear up for this pandemic in record time and “flattened the curve” efficiently:

How South Korea accelerated its coronavirus testing, while early missteps left the U.S. lagging far behind, is a story of flexibility, preparedness and painful lessons from a past fumble.

Much of South Korea’s current disease control response system was forged after a 2015 local outbreak of Middle East respiratory syndrome, or MERS, caused by a different coronavirus. At the time, the Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention found itself unable to handle the abrupt surge in demand for tens of thousands of tests amid the largest outbreak outside of Saudi Arabia, which ultimately killed 38 patients and infected nearly 200.

The experience prompted the country to overhaul its CDC and pass laws to prepare for the next epidemic. Central to the changes was the ability to cut through a bureaucratic months-long process to get test kits rapidly approved and working during an emergency. The Zika virus epidemic of 2016 served as a small-scale dry run of the new system.

As luck would have it, last December, the South Korean government held a mock disease response drill — under the premise of a coronavirus outbreak.

By Jan. 11, when China had reported just 41 cases and the WHO was discounting the prospect of human-to-human transmission, South Korea was distributing tests even though it wasn’t yet possible to test for the specific strand of the novel coronavirus causing the outbreak in Wuhan. By Jan. 31, with seven known cases in South Korea, test kits based on the virus’ genetic code released by China had been distributed to local government labs across the country.

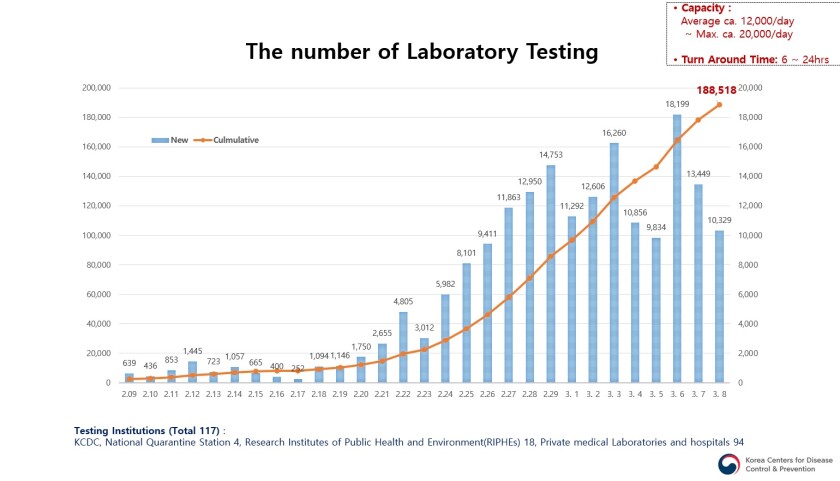

By the time authorities discovered a large cluster of thousands of infections in the southeastern city of Daegu in late February, the network of public health institutions and private labs and hospitals was prepared.

Early on, officials dropped the requirement that patients had to have traveled abroad in order to be tested, a criteria that has been an impediment to testing in America. When it became clear many of those who had attended the services of an obscure religious sect had been infected, authorities tested all of those with symptoms among the church’s more than 200,000 members. When outbreaks developed at a psych ward and at a call center, authorities called for a nationwide survey of all locked psych wards and all call centers. Officials also began screening all pneumonia patients with no known causes for the novel coronavirus.

Hong Ki-ho, director of laboratory medicine at Seoul Medical Center, who is also a member of the COVID-19 task force at the Korean Society of Laboratory Medicine, said Korea’s CDC, private labs and manufacturers had all contributed to the unprecedented scale-up of testing.

“It feels like a miracle that it all came together like this,” he said, noting the chaos and confusion the delays in testing caused during the MERS outbreak. “It’s so many times the scale of what it was during MERS, and we had so little time to prepare.”

Another key component of South Korea’s response is making tests free for the vast majority of those who have been screened, and covering the cost of their hospitalization and treatment. Even those who request a test without a doctor’s note can do so at the moderate cost of about $130.

After a peak in late February, when the number of infections was jumping by as many as 900 cases a day, the pace of new infections in South Korea has slowed to about 100 new cases reported Saturday. With new clusters being discovered in the densely packed Seoul metropolitan area this week, South Korea still faces challenges.

That hasn’t stopped the country from holding itself out as a model for other nations, highlighting the fact that it appears to be gaining a handle on the outbreak without the drastic travel restrictions China, the U.S. and other countries have imposed on their citizens.

“Public trust can only be earned and harnessed through full openness and transparency,” Lee Tae-ho, vice minister of foreign affairs, told reporters. “This public trust has resulted in a very high level of civic awareness and voluntary cooperation that strengthens our collective effort to overcome this public health emergency.”

I have a sneaking suspicion that the pandemic team that Bolton and Trump disbanded might have learned from the South Korean experience with MERS as well and would have launched into action earlier too. They had learned from H1N1 and Ebola here as well so there’s every reason to believe they could have marshaled a much more effective federal response than we got from Trump who just wanted to keep his “trade deal” going and his “numbers” down.

Heckuva job, Boltie.