Slate’s Lili Loofbourow frames Donald Trump’s movement of white nationalists and conspiracy cranks in a way I had not considered. Like Black Panther’s vibranium suit, the more ridicule cranks absorb the more powerful they become in a social-media world. Over-the-top craziness draws eyeballs. It upstages politicians and shifts the balance of power to the point that “laughing at a crank inflates his or her currency.” Makes them relevant. Turns them from “targets into lightning rods.”

Commenting on Rudy Giuliani’s election fraud sideshow in Michigan (and his viral star witness), Loofbourow writes:

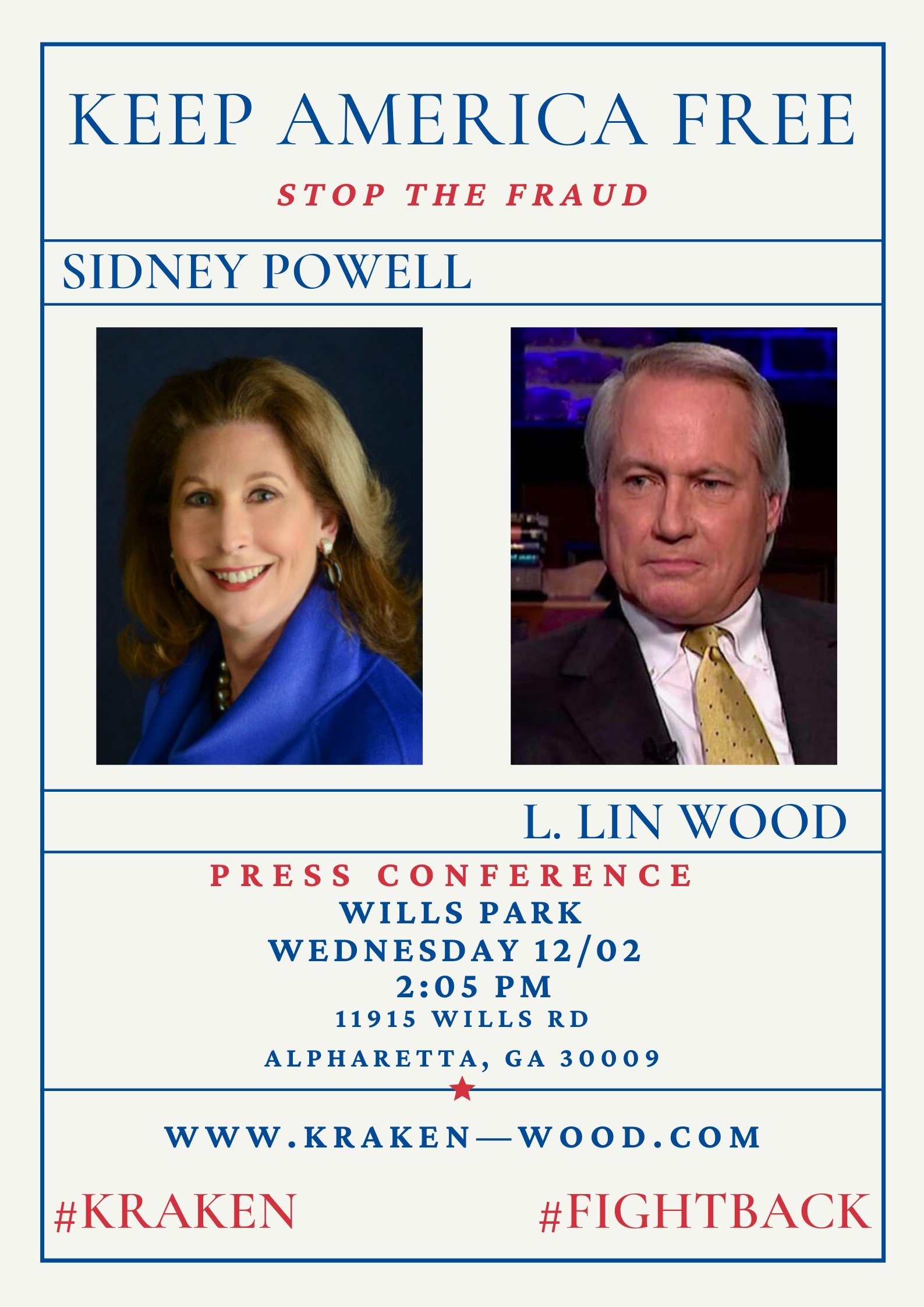

Cranks matter now. They are being given seats at the table, not just as witnesses but as officials. The president is a crank. So is his team, which is trying to overthrow the results of the election. Sidney Powell is a crank. Rudy Giuliani is a crank. QAnon cranks have been elected to Congress. If Donald Trump has proven anything, it’s that a massive number of Americans don’t have a “bridge too far” when it comes to crankish excesses we still somehow think the public will find disqualifying. If anything, the opposite is true: Cranks who proudly own their eccentricities and brandish them have learned that much of the American public will perceive their success despite their crankishness as proof of their power.

Cranks possess a peculiar kind of American “authenticity,” Loofbourow writes, “a type as confident as it is ignorant, so righteous and blustery and simultaneously sincere and unhampered by facts or deference that it makes terrific TV.”

This echoes how Bill McKibben described American evangelicals a decade and a half ago:

The power of the Christian right rests largely in the fact that they boldly claim religious authority, and by their very boldness convince the rest of us that they must know what they’re talking about. They’re like the guy who gives you directions with such loud confidence that you drive on even though the road appears to be turning into a faint, rutted track. But their theology is appealing for another reason too: it coincides with what we want to believe.

As Digby has long said, shamelessness is their superpower.

Loofbourow continues:

Never mind Trump’s ignorance, his conspiracy-mongering, or his con jobs. Trump’s hair, like his makeup, is a loud external expression of nonconformity that his followers respond to precisely because it’s ridiculous. That it will court mockery is obvious, but indifference to mockery is power. The more they’re mocked, the more followers double down into hurricanes of tribalism that become a sincere and unshakeable loyalty. It’s why they claim him as theirs rather than relegate him to just another Manhattan millionaire. The memes of Trump’s head pasted on muscular bodies are expressive of the way satire collapsed into sincerity—they are ridiculous but also completely serious: Trump supporters know he is an old man who prefers riding in golf carts to walking, but celebrate him as the healthy and powerful epitome of American masculinity.

Yale history professor Beverly Gage draws parallels between Trump’s movement and Sen. Joseph McCarthy’s. During the Red Scare, most Republicans displayed similar cowardice in failing to confront McCarthy’s threat to “democratic institutions and political fair play.” But as other Americans saw it, “the sheer volume of criticism aimed at the senator became proof that he was right all along: that the country was, indeed, run by a menacing but elusive liberal-communist conspiracy aimed at taking down right-thinking, God-fearing Americans.”

So that even with McCarthy’s downfall after “four years of lies and vitriol,” the resentments he stirred — supported by nearly half of Americans — spawned a new generation of right-wing activists, Gage explains:

After McCarthy’s censure, this tale — of a courageous warrior taken down by illegitimate foes — helped fuel a wave of institution-building on the right. In 1955, Buckley founded National Review magazine, a bid, as he described it, to break up the “identifiable team of Fabian operators” who were “bent on controlling both our major political parties.” Three years later, candy manufacturer Robert Welch established the John Birch Society, a conspiratorial far-right organization that attracted millions of members with claims that even Eisenhower secretly sympathized with communism. The two camps never saw eye to eye, with Buckley sneering at the Birchers’ paranoid style. When it came to McCarthy, though, they shared a common view: Though Buckley expressed certain reservations about the senator’s methods, he agreed that McCarthy’s censure in 1954 revealed the workings of a corrupt, soft and traitorous political establishment.

McCarthy managed to rise to stardom even with the opposition of media gatekeepers. Modern conspiracists have no such limitations. Trump’s movement may last far beyond Trump himself, Gage warns.

But I must point out once again the unintended consequences of seemingly benign, seemingly non-ideological technological advancements. TV, cars, the Internet, Facebook. The supposed decay of the atomic family decried by conservatives since the 1950s was not the product of teaching Marxism or eliminating official prayer in public classrooms. Automobiles made possible urban sprawl and bedroom communities. People could work miles away in one direction, go to church miles away in another; and school and play, etc. TV’s made it possible for families to entertain themselves inside the house rather than seek community out in the neighborhood. Societal changes are not always the products of the Devil or more terrestrial dark forces. Faceless technologies we adopt without weighing the costs. TV enabled the rise of Trump, the reality-TV president followed by a movement raised on it. Who could have seen that coming when a certain autocrat televised the opening of the Berlin Olympics in 1936?

In addition to bypassing big-media gatekeepers, social media allows the darker side of human nature to flourish and spread like a virus. “The fact is we’re in a crank pandemic and there’s no vaccine,” Loofbourow concludes. Like the coronavirus, Trumpism may be with us a while longer.