Poetry not prose

by Tom Sullivan

“That won’t work down South,” the consultant said not in those exact words.

I’d managed an invitation to a private, side event at the 2012 DNC convention in Charlotte. It was the kickoff party for a project supposed to marry data and micro-targeting with messaging somehow. The presenters were well-intentioned political activists who’d found a way to monetize their hobby the way New Age mantra-preneurs did with their spiritual journeys. The former Hill staffer-turned-consultant was there with local movers and shakers looking for a data-driven shortcut out of the wilderness. The 2010 midterms had been a slaughter.

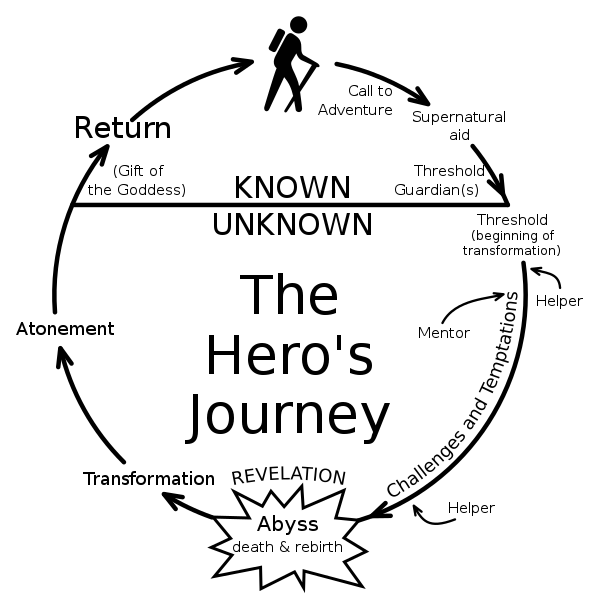

The presentation felt more like New Dem than born-again progressive. Asked if this was related somehow to a narratives project in Washington state, the consultant said he knew about that. But, he said, the “heroes and villains” stuff wouldn’t work in the South. “Meet Dr. [Joseph] Campbell,” a friend remarked later, noting that the Celtic ballads ubiquitous across the South are straight-up heroes-and-villains stories. The “Star Wars” saga is built on that foundation. Hollywood writers make their livings from crafting compelling stories and wonder at Democrats who place so much confidence instead in technological terrors.

Which brings us to Mark McKinnon’s 2016 post-mortem at Daily Beast. McKinnon is a media consultant who has worked for both Democrats and Republicans. “I’ve always believed there should be at least a little bit of art along with science in politics and life,” he writes. McKinnon feels that what Clinton lacked and Donald Trump had was a compelling narrative:

Trump told a story. We think about story usually in a cultural frame: movies, books, music. But it’s just as true for campaigns. Voters are attracted to candidates who lay out a storyline. Losing campaigns communicate unconnected streams of information, ideas, speeches. Winning campaigns create a narrative architecture that ties it all together into something meaningful and coherent, as I articulated last year in a short New York Times op-documentary.

How do you tell a story? Identify a threat and/or an opportunity. Establish victims of the threat or denied opportunity. Suggest villains that impose the threat or deny the opportunity. Propose solutions. Reveal the hero.

Not that Trump’s story was that coherent, but it was a story.

That’s what Trump did. The reality TV star understands the power of narrative. He identified a threat: outside forces trying to change the way we live. And an opportunity: make America great again. He established victims: blue-collar workers who have lost jobs or experienced a declining standard of living. He suggested villains: Mexican immigrants, China, establishment elites. He proposed solutions: build a wall, tear up unfair trade deals. And the hero was revealed, Donald Trump.

Hillary Clinton offered issues, prescriptions and policies. “Campaigning and governing demand different skill sets,” McKinnon writes. “Hillary Clinton was as qualified as anyone who has ever run for the office of president.” But where Bill “campaigns in poetry … she campaigns in prose.” That moment in 2008 when she let her guard down and teared up in New Hampshire after losing Iowa showed her to be authentically human says McKinnon (and everyone I know who has met her up close). That moment erased a double-digit deficit in 24 hours and she won New Hampshire.

McKinnon asks what I’ve been asking, “Why didn’t that lesson stick?”

My day job is in technology. But as McKinnon says, my job involves a little bit of art along with science. Yes, I use a computer and some high-dollar software. But it’s basically a fancy calculator to confirm a design I know will work from experience. Most of what I do is by “feel.” Democrats need to turn off the targeting computer and trust their feelings more.